When procurement teams evaluate quotes for custom corporate gift boxes, the decision framework typically reduces to a simple comparison: which supplier offers the lowest per-unit cost? A quote from Supplier A at 1,000 pieces for AED 85 per unit appears more expensive than Supplier B's 5,000-piece offer at AED 52 per unit, which in turn seems costlier than Supplier C's 10,000-piece pricing at AED 38 per unit. The arithmetic is straightforward, and the conclusion feels obvious—commit to the highest volume to secure the lowest per-unit cost.

This is where the misjudgment begins. The per-unit cost comparison omits a critical variable: tooling cost amortization. Custom gift box production requires upfront investment in dies, plates, and setup configurations that remain fixed regardless of order volume. When these tooling costs are separated from per-unit pricing—as they often are in supplier quotes—procurement teams struggle to calculate the true break-even point between inventory risk and cost savings. The result is a systematic pattern of either over-committing to volumes that exceed actual distribution needs or under-committing to quantities that fail to recover tooling investments efficiently.

The core issue is not that procurement teams lack cost-consciousness. Rather, it is that the cost structure of custom packaging does not behave linearly, and the inflection points where volume commitments shift from prudent to excessive are not intuitively obvious without understanding how tooling costs distribute across production runs.

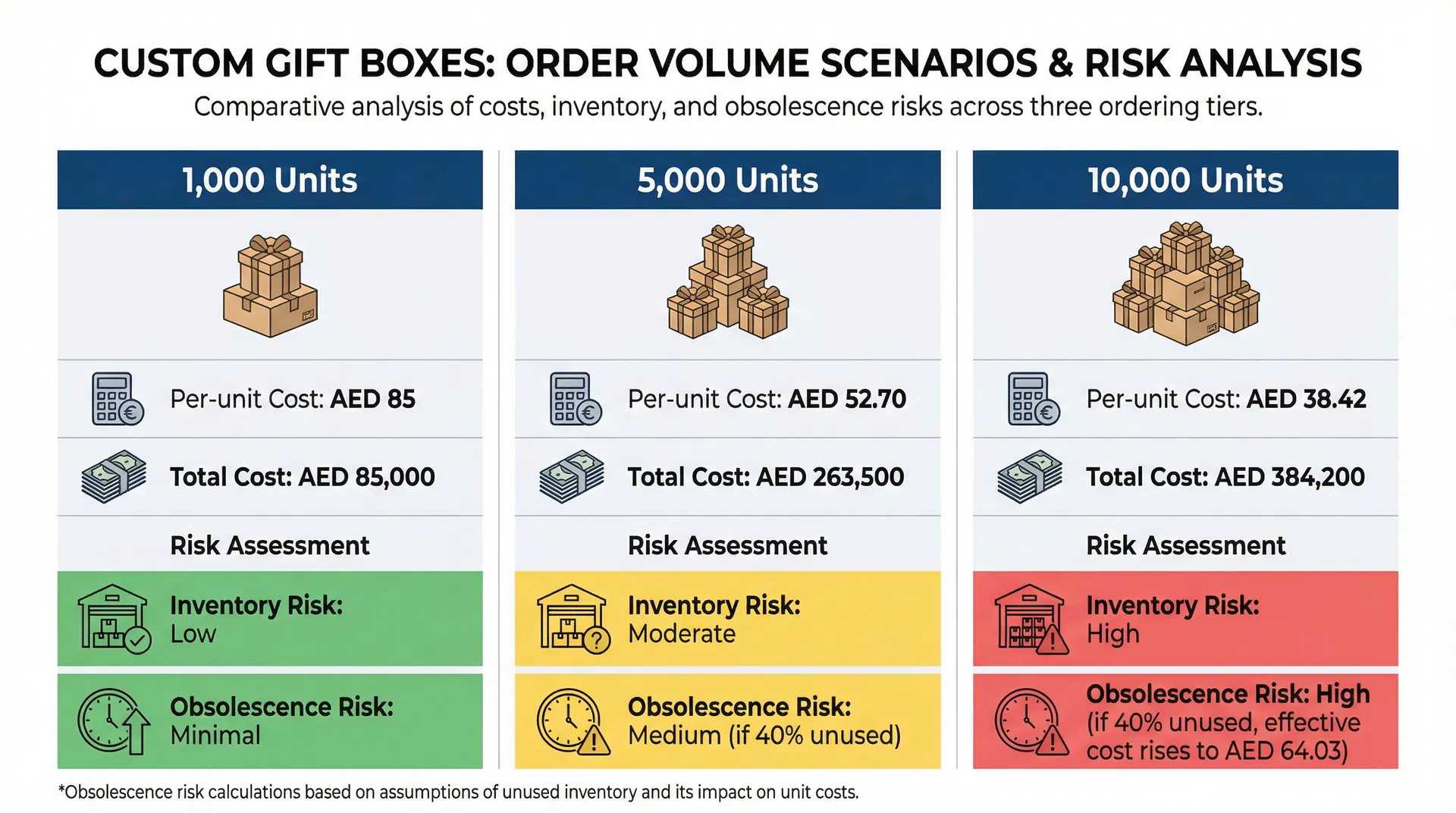

Consider a representative scenario from UAE corporate gifting. A procurement manager receives three quotes for a custom rigid gift box with magnetic closure, soft-touch lamination, and foil stamping. Supplier A quotes 1,000 pieces at AED 85 per unit with tooling included in the price. Supplier B quotes 5,000 pieces at AED 52 per unit, with AED 3,500 in separate tooling charges. Supplier C quotes 10,000 pieces at AED 38 per unit, with AED 4,200 in tooling costs listed separately.

At first glance, Supplier C offers the lowest per-unit cost. But when tooling is factored in, the total cost per unit becomes AED 38.42 for Supplier C, AED 52.70 for Supplier B, and AED 85.00 for Supplier A. Supplier C still appears most economical—until the procurement team considers whether they can actually distribute 10,000 units before the gift program concludes, the design becomes outdated, or the recipient list changes.

This is the point where decisions about custom corporate gift box specifications begin to diverge from sound financial analysis. Teams focus on minimizing the visible per-unit cost without systematically evaluating the hidden costs of volume commitment: inventory carrying costs, obsolescence risk, and the opportunity cost of capital tied up in unused stock.

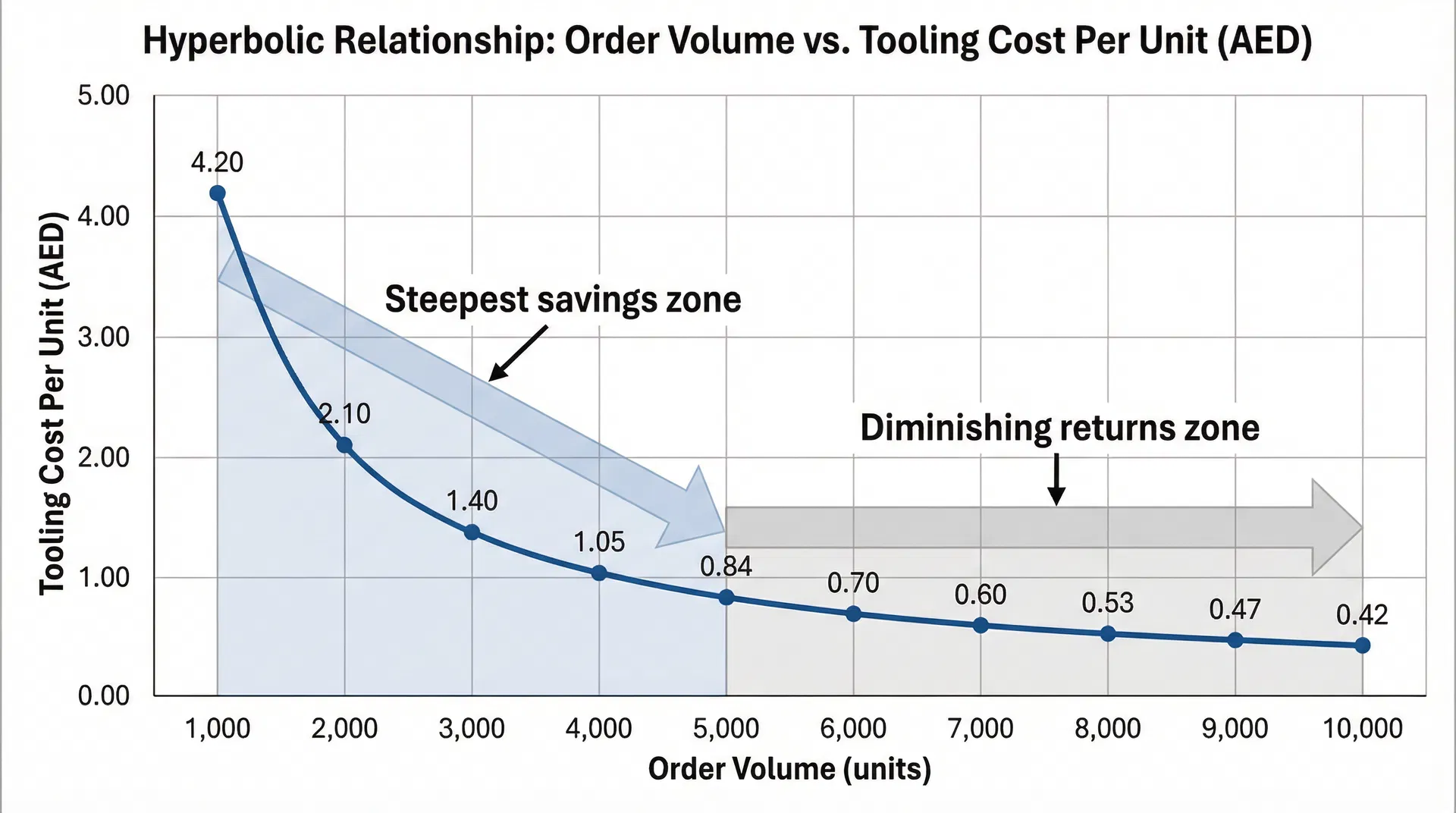

Tooling cost recovery follows a hyperbolic curve, not a linear progression. The first 1,000 units absorb tooling costs at a rate of AED 4.20 per unit (using Supplier C's tooling fee as an example). The next 1,000 units reduce that burden to AED 2.10 per unit. By the time production reaches 5,000 units, tooling cost per unit drops to AED 0.84. Beyond 10,000 units, the incremental benefit of additional volume diminishes rapidly—tooling cost per unit falls to AED 0.42, a reduction of only AED 0.42 compared to the AED 3.36 saved by moving from 1,000 to 10,000 units.

The practical implication is that the steepest cost savings occur in the early volume tiers, and the marginal benefit of committing to higher volumes flattens significantly once tooling costs are sufficiently amortized. Yet procurement teams often treat volume decisions as if the cost curve were linear, assuming that doubling order size will proportionally double savings. This assumption leads to over-ordering when the actual cost benefit no longer justifies the inventory risk.

The second misjudgment involves inventory carrying costs and obsolescence risk. Corporate gift programs in the UAE market are frequently tied to specific events—Ramadan gifting, year-end client appreciation, new office openings, or VIP relationship milestones. These programs have defined timelines, and gift box designs are often customized with event-specific branding, messaging, or seasonal themes. Ordering 10,000 units to capture a AED 14 per-unit savings (compared to 5,000 units) makes financial sense only if all 10,000 units will be distributed within the program's active period.

If the procurement team distributes 6,000 units and stores the remaining 4,000 for future use, those units incur warehouse rental costs, handling fees, and the risk of becoming obsolete if the company rebrands, the design falls out of favor, or the recipient list changes. In the UAE market, where corporate gift trends shift rapidly and brand refresh cycles are frequent, the risk of obsolescence is not hypothetical. We have observed procurement teams sitting on 3,000–5,000 units of custom gift boxes that can no longer be used because the company logo was updated, the product line was discontinued, or the gifting strategy shifted toward different recipient segments.

The financial impact of obsolescence is often underestimated. If 4,000 units become unusable, the effective cost per distributed unit rises from AED 38.42 to AED 64.03—higher than the per-unit cost of ordering 5,000 units in the first place. The apparent savings from committing to higher volume evaporate when obsolescence is factored in, yet procurement teams rarely build obsolescence probability into their volume decision models.

The third misjudgment concerns multi-SKU scenarios. Corporate gift programs frequently require multiple variants—different box sizes for different gift tiers, localized designs for different regional offices, or product-specific packaging for different client segments. When a procurement team needs three different gift box designs, each with its own MOQ requirement, the volume commitment compounds rapidly.

If each design requires a 5,000-unit MOQ, the total commitment becomes 15,000 units. If the procurement team only needs 3,000 units of each design (9,000 total), they face a choice: accept a 67% over-order to meet MOQ requirements, or negotiate split production runs that increase per-unit costs by 20–30%. Neither option is ideal, but the decision is rarely framed in terms of total cost of ownership. Instead, procurement teams focus on meeting MOQ thresholds without systematically evaluating whether the resulting inventory levels align with distribution capacity.

Some suppliers offer "order splitting" to accommodate lower volumes—producing 2,000 units now and 3,000 units later to meet a 5,000-unit MOQ. This appears to solve the inventory problem, but it introduces hidden costs. Split orders often result in color batch variations, as the second production run may use a different ink or material lot. Delivery timing becomes less predictable, as the supplier must schedule the second run around other production commitments. And if the procurement team decides not to proceed with the second batch, they forfeit the per-unit cost savings that justified the MOQ commitment in the first place.

The fourth misjudgment involves tooling reuse assumptions. Procurement teams often view tooling as a one-time investment that can be leveraged across multiple orders. If the company orders 5,000 units now and pays AED 3,500 in tooling costs, the assumption is that future orders can reuse the same tooling without incurring additional setup fees. This assumption holds only if the design, materials, and supplier remain unchanged.

In practice, tooling becomes obsolete more frequently than procurement teams anticipate. A minor design revision—adjusting the box dimensions by 5mm, changing the closure mechanism from magnetic to ribbon-tie, or switching from soft-touch lamination to matte finish—often requires new tooling. If the company switches suppliers to secure better pricing or faster lead times, the original tooling cannot be transferred, and the new supplier must create fresh dies and plates. Even if the design and supplier remain constant, tooling degrades over time, and suppliers may charge refurbishment fees or require new tooling after 18–24 months of storage.

The result is that tooling costs, which procurement teams treat as a one-time expense, often recur with each subsequent order. The total cost of ownership calculation must account for the probability of design changes, supplier switches, and tooling degradation—factors that are difficult to quantify but materially affect the break-even analysis.

The systematic error in volume commitment decisions stems from a mismatch between the cost structure of custom packaging and the decision frameworks procurement teams apply. Teams are trained to minimize per-unit costs, but custom packaging economics reward volume commitments only up to the point where tooling costs are efficiently amortized and inventory risk remains manageable. Beyond that point, additional volume generates diminishing returns and exposes the company to obsolescence risk that can erase the apparent savings.

A more rigorous approach requires procurement teams to calculate total cost of ownership across different volume scenarios, incorporating tooling amortization, inventory carrying costs, obsolescence probability, and the likelihood of design changes or supplier switches. The break-even point is not the volume tier with the lowest per-unit cost—it is the volume tier where the marginal cost savings from additional units no longer justify the incremental inventory risk and capital commitment.

For UAE enterprises managing corporate gift programs, this means resisting the instinct to maximize volume commitments purely to minimize per-unit costs. It means building obsolescence risk into the financial model, accounting for the compounding effect of multi-SKU MOQ requirements, and recognizing that tooling costs may recur more frequently than anticipated. The goal is not to secure the lowest possible per-unit price—it is to identify the volume commitment that optimizes total cost of ownership while maintaining distribution flexibility and minimizing obsolescence exposure.

The procurement teams that navigate this decision most effectively are those that treat volume commitments as risk management decisions, not cost minimization exercises. They recognize that the steepest cost savings occur in the early volume tiers, and that pushing beyond the efficient amortization point often generates more risk than reward. They build contingency into their volume planning, accounting for the possibility that not all units will be distributed as planned. And they maintain realistic expectations about tooling reuse, understanding that design changes and supplier switches are common enough to treat tooling as a recurring cost rather than a one-time investment.

The break-even miscalculation in custom gift box procurement is not a failure of arithmetic—it is a failure to account for the non-linear cost structure of custom packaging and the hidden costs of volume commitment. Correcting this misjudgment requires procurement teams to shift from per-unit cost comparison to total cost of ownership analysis, incorporating tooling amortization curves, inventory risk, and obsolescence probability into their decision models. The result is a more disciplined approach to volume commitments that balances cost efficiency with operational flexibility, reducing the likelihood of over-ordering while ensuring that tooling investments are recovered efficiently.

Related Articles

Understanding the Customization Process for Corporate Gift Boxes

A comprehensive guide to navigating the customization journey for premium corporate gift packaging.

Material Specification vs Final Appearance

Why material specifications don't guarantee consistent visual outcomes in custom gift box production.