There is a persistent belief among procurement teams that providing a physical reference sample to a factory eliminates the need for detailed written specifications. The reasoning seems sound: if the factory can hold the object, examine its construction, feel its materials, and observe its finish, then surely the production team understands exactly what is expected. In practice, this assumption is one of the most reliable sources of specification disputes in custom gift box projects. The reference sample does not communicate intent. It communicates an artifact—and the factory reads that artifact through the filter of what it can produce, what it has produced before, and what it assumes the client will accept.

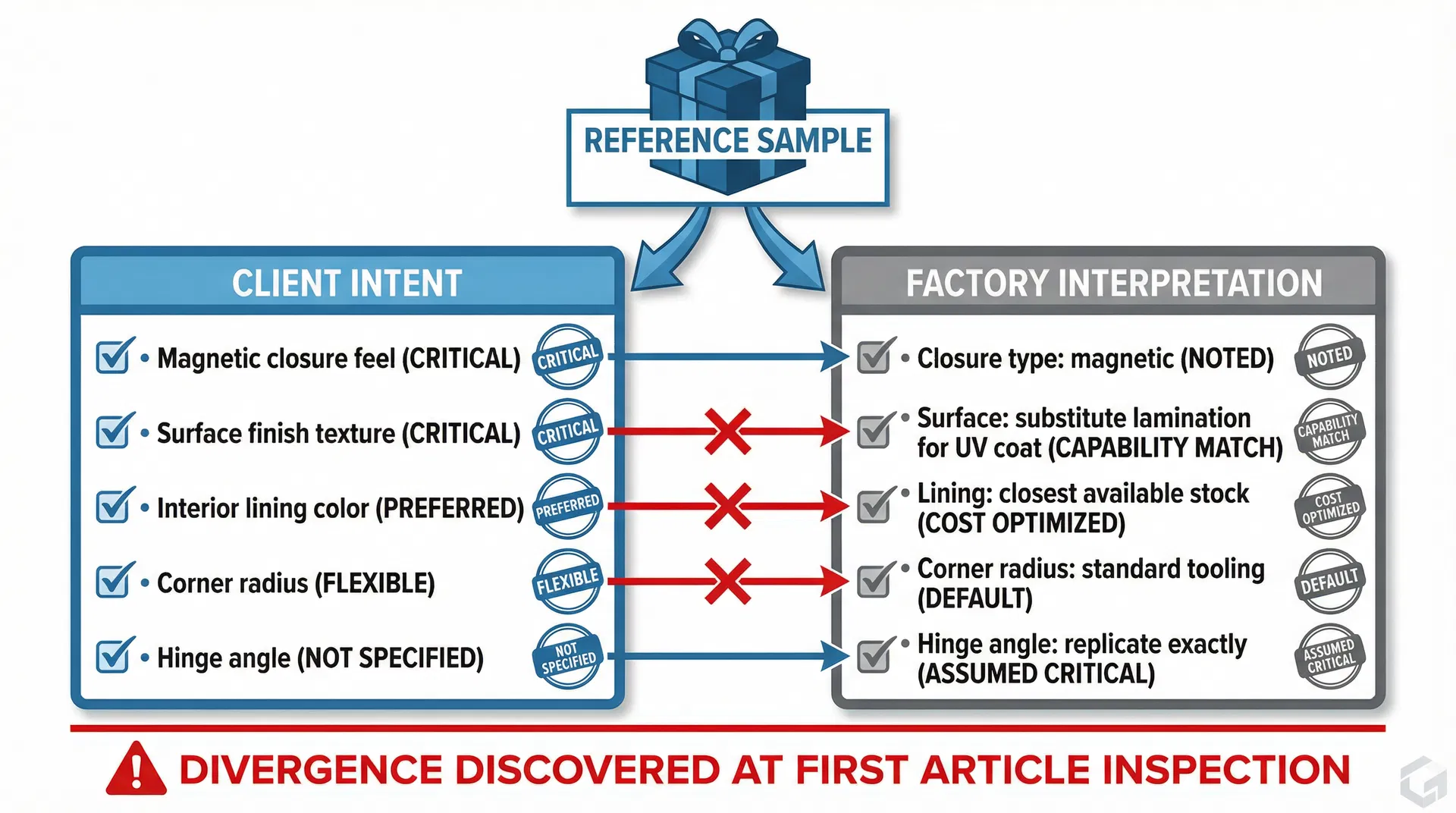

The core problem is that a physical sample contains far more information than the client intends to specify. When a procurement manager hands over a competitor's gift box or a sample from a previous supplier, they typically mean to communicate a narrow set of attributes: perhaps the closure mechanism, the wall thickness, or the surface finish. But the factory receives the entire object—and it has no reliable way to distinguish which attributes are intentional requirements and which are incidental artifacts of the original manufacturer's process. The hinge angle, the glue line visibility, the internal corner radius, the grain direction of the paper wrap, the precise shade of the lining fabric—all of these are present in the sample, and all of them are ambiguous in terms of whether the client considers them critical, acceptable, or irrelevant.

This ambiguity is compounded by a factory behavior that procurement teams rarely anticipate: capability-driven interpretation. When a factory examines a reference sample, it does not ask "what did the client intend?" It asks "how would we make this?" The factory's engineering team reverse-engineers the sample through the lens of their available tooling, their standard material inventory, and their established process sequences. If the reference sample was produced using a die-cutting method the factory does not have, the factory will silently substitute a laser-cutting approach that produces a visually similar but structurally different result. If the sample's surface finish was achieved through a UV coating process the factory typically avoids due to cost, the factory may default to a lamination process that approximates the visual effect but behaves differently under humidity and handling stress. None of these substitutions are communicated as deviations because, from the factory's perspective, they are not deviating—they are interpreting.

The divergence between client intent and factory interpretation typically surfaces at the worst possible moment: when the first production batch arrives. By that point, tooling has been fabricated, materials have been purchased, and production line time has been committed. The procurement team opens the delivery and discovers that the magnetic closure "feels different," the embossing depth is shallower than expected, or the box lid does not sit at the same angle as the reference. The factory's response is predictable and, from their perspective, entirely reasonable: "We matched the sample." What they mean is that they matched the sample as they understood it, within the constraints of their production system. The procurement team's unstated assumption—that certain attributes of the reference were non-negotiable—was never explicitly communicated because the team believed the sample itself was the communication.

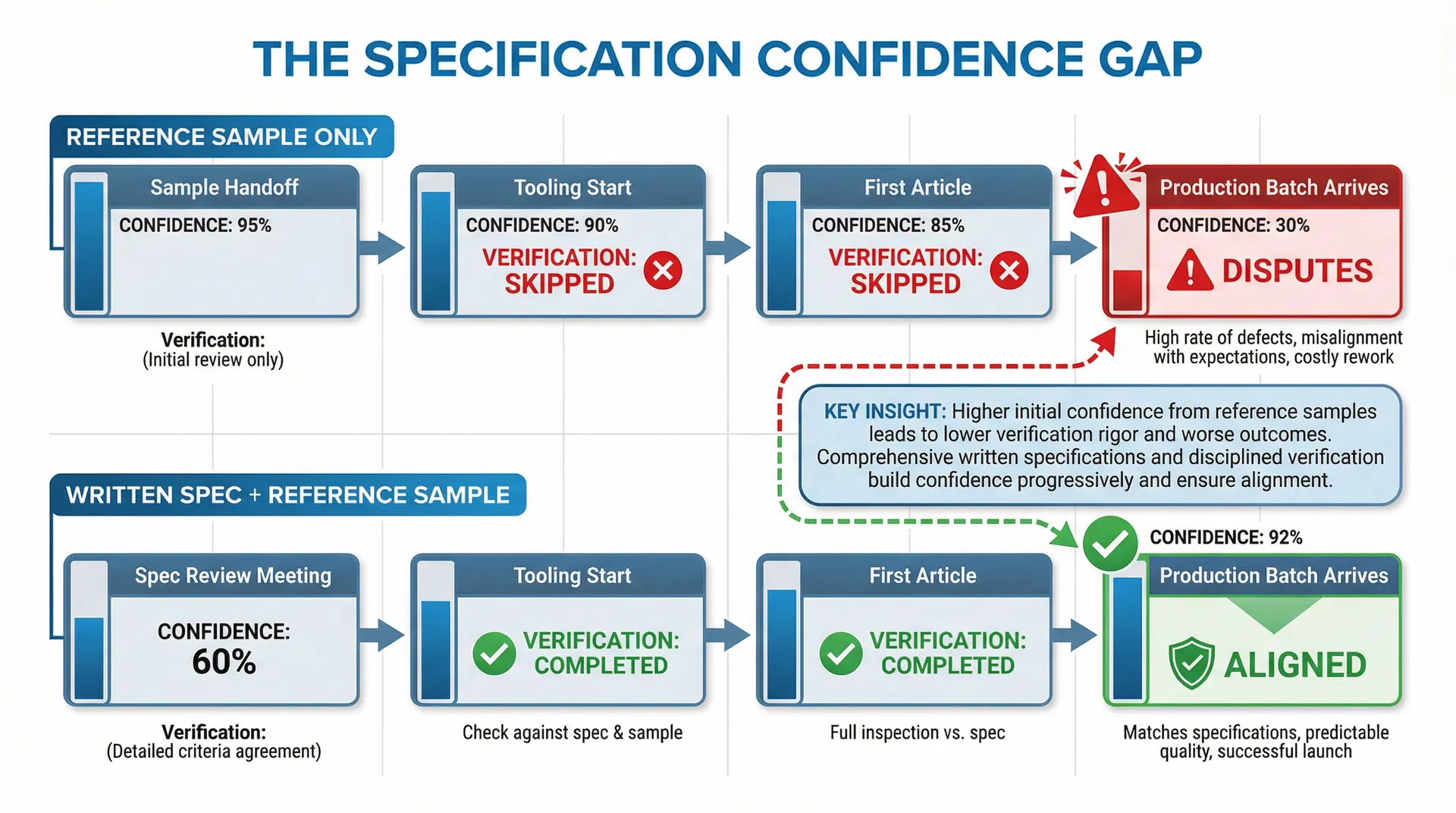

In practice, this is often where customization process decisions start to be misjudged. The reference sample creates what might be called a "specification confidence gap"—the procurement team's confidence in specification clarity is inversely proportional to the actual clarity of the specification. A team that provides only a written brief with dimensional tolerances and material grades knows it needs to verify factory understanding at every stage. A team that provides a physical sample often skips the verification steps entirely, assuming the sample has done the communication work for them. This confidence gap is particularly dangerous in custom gift box projects because the attributes that matter most to the client—tactile quality, perceived weight, opening resistance, visual harmony between components—are precisely the attributes that are hardest to reverse-engineer from a physical sample and easiest for a factory to reinterpret.

The problem deepens when the reference sample comes from a different manufacturer or a different production geography. A gift box produced in a Japanese facility using specific paper stocks, adhesive systems, and finishing equipment will exhibit characteristics that are inseparable from that facility's production ecosystem. When a UAE-based procurement team provides this sample to a Chinese or Indian manufacturer, the factory is being asked to replicate an outcome that was produced by a fundamentally different set of capabilities. The factory will attempt to match the visual result, but the underlying construction—the things that determine how the box ages, how it performs under shipping stress, how it feels in the recipient's hands—will reflect the producing factory's own methods and materials. The procurement team may not notice these differences during a quick inspection of the first article sample, but the end recipient almost certainly will when they compare the gift box to the brand experience they were promised.

There is also a temporal dimension to this problem that procurement teams frequently overlook. A reference sample represents a moment in time—a specific production run using specific material batches. Materials evolve. Paper suppliers reformulate coatings. Fabric dye lots shift. Adhesive chemistries change to meet updated environmental regulations. Even if the factory could perfectly replicate the reference sample's construction method, the materials available today may produce a subtly different result than the materials that were available when the reference was manufactured. The procurement team treats the sample as a fixed specification, but the factory treats it as an approximation target, knowing that exact material matching across time and across suppliers is rarely achievable without explicit material specifications that go beyond "match the sample."

The operational consequence is that reference-sample-driven projects tend to generate more revision cycles, more first-article rejections, and more mid-production disputes than projects that invest upfront in detailed written specifications supplemented by the reference sample as an illustrative aid rather than a definitive standard. When teams approach the complex decision environment of custom gift box customization, the reference sample should function as a conversation starter, not a conversation replacement. It should prompt a structured dialogue between the procurement team and the factory about which attributes are critical, which are preferred, and which are flexible—and that dialogue needs to be documented in a specification sheet that both parties sign before tooling begins.

The most effective mitigation is not to stop using reference samples—they remain valuable communication tools—but to change the role they play in the specification process. Instead of handing over a sample and saying "make this," the procurement team should hand over the sample alongside a marked-up annotation document that explicitly identifies: which attributes of the sample are mandatory requirements, which are directional preferences, and which are irrelevant artifacts of the original production process. This annotation forces the procurement team to articulate their own priorities before the factory begins interpretation, and it gives the factory a framework for asking targeted questions rather than making silent assumptions. Without this framework, the factory's interpretation will always default to whatever is easiest and cheapest to produce within its existing capability set—which is rarely what the client had in mind.

The deeper issue is organizational. Procurement teams that rely heavily on reference samples are often teams that have not developed the internal vocabulary to describe what they actually want. They know the box should "feel premium" but cannot specify the wall thickness, board grade, and surface treatment combination that produces that feeling. They know the closure should be "satisfying" but cannot define the magnetic pull force, the lid travel distance, or the dampening resistance that creates that sensation. The reference sample becomes a proxy for specification competence—and like most proxies, it introduces systematic distortion. Until procurement teams invest in building the technical language to describe their requirements independently of any physical artifact, the reference sample will continue to function as a source of false confidence rather than genuine specification clarity.